"Das Beste, was wir von der Geschichte haben ist der Enthusiasmus, den sie erregt." - J.W. Goethe

"If you know your history, Then you would know where you coming from." - Bob Marley

This section elaborated on the historical overview given on the previous 'INDO History Overview' page.

This section elaborated on the historical overview given on the previous 'INDO History Overview' page.

History In Depth

Indo people (short for Indo-European) are a Eurasian people of mixed Indonesian and European descent. Through the 16 and 18th century known by the name Mestiço (Dutch: Mestiezen). To this day they form one of the largest Eurasian communities in the world.

The early beginning of this community started with the arrival of Portuguese traders in South East Asia in the 16th century. The second large wave started with the arrival of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) employees in the 17th century and throughout the 18th century. Even though the VOC is often considered a state within a state, formal colonisation by the Dutch only commenced in the 19th century. The below chapters help give a better understanding on how Indos became a social outgroup in their own native land, leading to the Indo Diaspora . |

Content

|

Indos in pre-colonial history (16th, 17th and 18th century)

The pre-colonial Portuguese Indos

Before the formal colonization of the East Indies by the Dutch in the 19th century, the islands of South East Asia had already been in frequent contact with European traders. Portuguese maritime traders were present as off the 16th century. Around its trading posts the original Portuguese Indo population, called Mestiço, had developed. In the 17th century the Dutch started to expand its mercantile enterprise and military presence in the East Indies in an effort to establish trade monopolies to maximise profit. Even after the Portuguese competition was beaten by the Dutch maritime traders of the VOC, the Portuguese Indo (aka Mestiço) communities remained active in local and intra-island trade. The Dutch found merit in collaboration with these early Eurasian communities through their role as intermediaries with local traders, but also to help mitigate the threat of the encroaching British traders. Up to the first century of Dutch (VOC) dominance the cultural influence of the Portuguese Indo population continued as can be seen by the fact that Portuguese Malay mix languages remained in existence well into the second century of the VOC era and autonomous Portuguese Indo groups existed into the 19th century.

Portuguese roots of Indo society

Originally the greatest source of profit in the East Indies, was the intra islands trade within the archipelago (Dutch: inlandse handel) and the intra-Asiatic trade in general. Here one commodity was exchanged for another, with profit at each turn. This included the trade of silver from the Americas, more desirable in the East than in Europe. In this trade the original Indo or Mestizo population remained to play an intermediary role.

The VOC made good use of such (Indo) people, born and brought up locally. They could speak the language of their birth country and understood its conventions, and proved excellent middlemen for the Europeans. For the same reason these Eurasians were extremely useful for Asian rulers. Historian Ulbe Bosma.

Even long after the Dutch had defeated and expelled their Portuguese competition from the islands, the language of trade remained the Malay/Portuguese mix language, which is reflected in the relatively many Portuguese words that survive in the Indonesian language to this day. The census taken of the population of Ambon island in 1860, still showed 778 Dutch Europeans and 7793 mostly Mestiço and Ambonese 'Burghers'. Portuguese/Malay speaking Indo communities existed not only in the Moluccas, Flores and Timor. But also in Batavia (now Jakarta) where it remained the dominant language up to 1750.

Portuguese Creole Language

For the Mestizo-Indo of the pre-colonial era their first language was often the Portuguese creole language called Portugis, based on Malay and Portuguese. It remained the dominant lingua franca for trade throughout the archipelago from the sixteenth century through to the early nineteenth century. Many Portugis words survive in the Indonesian language including: sabun (from sabão = soap), meja (from mesa = table), boneka (from boneca = doll), jendela (from janela = window), gereja (from igreja = church), bola (from bola = ball), bendera (from bandeira = flag), roda (from roda = wheel), gagu (from gago = stutterer), sepatu (from sapato = shoes), kereta (from carreta = wagon), bangku (from banco = chair), keju (from queijo = cheese), garpu (from garfo = fork), terigu (from trigo = flour), mentega (from manteiga = butter), Minggu (from domingo = Sunday) and Belanda (from Holanda = Dutch).

The word Sinyo (from Señor) was used for Indo boy and young man and the word Nona or the variation Nonni (from Dona) for Indo girls or young women. In yet another derivation of the original Portuguese word that means lady a mature Indo woman was called Nyonya, sometimes spelled Nonya. This honorific loan word came to be used to address all women of foreign descent.

Mardijker people

Another notable Portuguese/Malay speaking group were the Mardijker people, which the VOC legally acknowledged as a separate ethnic group. Most of them were freed Portuguese slaves with ethnic roots in India, but of Christian faith. Eventually the term came into use for any freed slave and is the word from which the Indonesian word 'Merdeka' meaning freedom is derived.[19] This group and its descendants heavily inter-married with the Portuguese Mestiço community. Kampung Tugu was a famous Mardijker settlement in Batavia, but Mardijker quarters could be found in all major trading posts including Ambon and Ternate.[20] The majority of this group eventually assimilated completely into the larger Indo Eurasian community and disappear from the records. Into the 18th century Indo culture remained dominantly Portuguese/Malay in nature

Topasses people

An independent group of Mestiço of Portuguese descent were the Topasses people who were based in Solor, Flores and pre-dominantly Timor. The community in Larantuka on Flores called themselves Larantuqueiros. This powerful group of Mestiço controlled the sandalwood trade and strongly opposed the Dutch. They manifested themselves very independently and actually fought many wars with both the Dutch and Portuguese in the 17th and 18th century. Portuguese Mestiço that chose not to cooperate with the Dutch and VOC deserters often joined with the Topasses. This group eventually assimilated into the indigenous nobility and Eurasian elite of East Timor. Famous family clans are 'De Hornay' and 'Da Costa', that still exist as Timorese Raja to this day.

Before the formal colonization of the East Indies by the Dutch in the 19th century, the islands of South East Asia had already been in frequent contact with European traders. Portuguese maritime traders were present as off the 16th century. Around its trading posts the original Portuguese Indo population, called Mestiço, had developed. In the 17th century the Dutch started to expand its mercantile enterprise and military presence in the East Indies in an effort to establish trade monopolies to maximise profit. Even after the Portuguese competition was beaten by the Dutch maritime traders of the VOC, the Portuguese Indo (aka Mestiço) communities remained active in local and intra-island trade. The Dutch found merit in collaboration with these early Eurasian communities through their role as intermediaries with local traders, but also to help mitigate the threat of the encroaching British traders. Up to the first century of Dutch (VOC) dominance the cultural influence of the Portuguese Indo population continued as can be seen by the fact that Portuguese Malay mix languages remained in existence well into the second century of the VOC era and autonomous Portuguese Indo groups existed into the 19th century.

Portuguese roots of Indo society

Originally the greatest source of profit in the East Indies, was the intra islands trade within the archipelago (Dutch: inlandse handel) and the intra-Asiatic trade in general. Here one commodity was exchanged for another, with profit at each turn. This included the trade of silver from the Americas, more desirable in the East than in Europe. In this trade the original Indo or Mestizo population remained to play an intermediary role.

The VOC made good use of such (Indo) people, born and brought up locally. They could speak the language of their birth country and understood its conventions, and proved excellent middlemen for the Europeans. For the same reason these Eurasians were extremely useful for Asian rulers. Historian Ulbe Bosma.

Even long after the Dutch had defeated and expelled their Portuguese competition from the islands, the language of trade remained the Malay/Portuguese mix language, which is reflected in the relatively many Portuguese words that survive in the Indonesian language to this day. The census taken of the population of Ambon island in 1860, still showed 778 Dutch Europeans and 7793 mostly Mestiço and Ambonese 'Burghers'. Portuguese/Malay speaking Indo communities existed not only in the Moluccas, Flores and Timor. But also in Batavia (now Jakarta) where it remained the dominant language up to 1750.

Portuguese Creole Language

For the Mestizo-Indo of the pre-colonial era their first language was often the Portuguese creole language called Portugis, based on Malay and Portuguese. It remained the dominant lingua franca for trade throughout the archipelago from the sixteenth century through to the early nineteenth century. Many Portugis words survive in the Indonesian language including: sabun (from sabão = soap), meja (from mesa = table), boneka (from boneca = doll), jendela (from janela = window), gereja (from igreja = church), bola (from bola = ball), bendera (from bandeira = flag), roda (from roda = wheel), gagu (from gago = stutterer), sepatu (from sapato = shoes), kereta (from carreta = wagon), bangku (from banco = chair), keju (from queijo = cheese), garpu (from garfo = fork), terigu (from trigo = flour), mentega (from manteiga = butter), Minggu (from domingo = Sunday) and Belanda (from Holanda = Dutch).

The word Sinyo (from Señor) was used for Indo boy and young man and the word Nona or the variation Nonni (from Dona) for Indo girls or young women. In yet another derivation of the original Portuguese word that means lady a mature Indo woman was called Nyonya, sometimes spelled Nonya. This honorific loan word came to be used to address all women of foreign descent.

Mardijker people

Another notable Portuguese/Malay speaking group were the Mardijker people, which the VOC legally acknowledged as a separate ethnic group. Most of them were freed Portuguese slaves with ethnic roots in India, but of Christian faith. Eventually the term came into use for any freed slave and is the word from which the Indonesian word 'Merdeka' meaning freedom is derived.[19] This group and its descendants heavily inter-married with the Portuguese Mestiço community. Kampung Tugu was a famous Mardijker settlement in Batavia, but Mardijker quarters could be found in all major trading posts including Ambon and Ternate.[20] The majority of this group eventually assimilated completely into the larger Indo Eurasian community and disappear from the records. Into the 18th century Indo culture remained dominantly Portuguese/Malay in nature

Topasses people

An independent group of Mestiço of Portuguese descent were the Topasses people who were based in Solor, Flores and pre-dominantly Timor. The community in Larantuka on Flores called themselves Larantuqueiros. This powerful group of Mestiço controlled the sandalwood trade and strongly opposed the Dutch. They manifested themselves very independently and actually fought many wars with both the Dutch and Portuguese in the 17th and 18th century. Portuguese Mestiço that chose not to cooperate with the Dutch and VOC deserters often joined with the Topasses. This group eventually assimilated into the indigenous nobility and Eurasian elite of East Timor. Famous family clans are 'De Hornay' and 'Da Costa', that still exist as Timorese Raja to this day.

Indos from the VOC era

VOC roots of Indo society

During the 200 years of the VOC era intermixing with indigenous peoples kept running its natural course. Over the years the VOC had sent out around 1 million employees, of which only one third returned to Europe. Its personnel consisted of mostly single men traveling without families.

The distance to Europe was far and transport still took a very long time. High mortality rates among its employees were common. To a degree racial mixing was even encouraged by the VOC, as it was aiming to establish a prominent and consistent presence in the East Indies. A considerable number of these men can be considered emigrant settlers, that had no intention of leaving the East Indies, creating their own local Indo Eurasian families.

Moreover the VOC needed larger European representation to run its local business and therefore stimulated growt in numbers of an Indo population of Dutch descent. These Indos played important roles as VOC officials. VOC representatives, called residents, at the royal courts were often Indos able to speak the indigenous languages.

Over the centuries of intensive Portuguese and Dutch trade with the islands of the East Indies a relatively large Indo Eurasian population developed. These old Indo families make up the native (Indonesian: Peranakan) stock of Europeans during the ensuing colonial era. Throughout formal colonisation of the Dutch East Indies in the coming century, the majority of registered Europeans were in fact Indo Eurasians.

Note: Oil painting depicting an Indo woman in traditional 'batik sarong kebaya' dress, an originally indigenous aristocratic dress style from the 16th century and commonly worn by Eurasian women well into the 20th century

Indo society during the VOC era

Pre-colonial Indo culture dominated the European segment of society in the East Indies. This culture was heavily Eurasian i.e. hybrid in nature and even the most high ranking Dutch VOC officials were absorbed by it. Indo society was polygot and its' first languages were Malay, Portugis and other creole languages, not Dutch. It was also matriarchal and most Europeans, even the VOC governor-generals would marry into Indo clans. Only by doing so they were able to obtain the necessary connections, patronage, wealth and know how.

"Women based clans absorbed the immigrant males who came without wives. the clan enfolded the newcomer in a network of immigrants with locally born wives, mestizo (Indo) and Asian (Indonesian) kin alike. In the same time the clan eased the adoption of Indies manners for the newcomers." Historian Jean Gelman Taylor in The social world of Batavia, European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia.

The arts and crafts patronized by the Indo elite were usually indigenous e.g. gamelan, batik, various court dances, etc. In their immediate personal habitat they were closely surrounded by indigenous servants. Overall lifestyle was similar to the indigenous elite. Women clothing was often indistinguishable from indigenous fancy dress and many practices were rooted in ancient indigenous court culture.

In an attempt to mitigate cultural dominance of Indo society the expatriate aristocrat baron van Imhoff (1705–1750), VOC governor from 1743 to 1750, founded several institutions to cultivate Dutch culture among the native colonial elite. His Naval Academy for maritime VOC officers in Batavia was exemplary in its' aim to foster western identity. Van Imhoff showed how well he understood the strength of the Indo-Europeans' indigenous derived beliefs and manners when he decreed that even the academy's cooks, stewards and servants were to be European. Another academy decree strictly stipulated: "There shall be no native tongues spoken in the house."

Next governors also vainly tried to introduce the Dutch language in the VOC operated schools and churches, but Portugis and Malay remained the dominant languages. Even the highest VOC officials were unable to pass on their own mother tongue to their offspring. In general the VOC had always recognised the tendency of its servants to be absorbed by the hybrid Indo culture and repeatedly issued regulations limiting higher company positions to men born in the Netherlands.

During the 200 years of the VOC era intermixing with indigenous peoples kept running its natural course. Over the years the VOC had sent out around 1 million employees, of which only one third returned to Europe. Its personnel consisted of mostly single men traveling without families.

The distance to Europe was far and transport still took a very long time. High mortality rates among its employees were common. To a degree racial mixing was even encouraged by the VOC, as it was aiming to establish a prominent and consistent presence in the East Indies. A considerable number of these men can be considered emigrant settlers, that had no intention of leaving the East Indies, creating their own local Indo Eurasian families.

Moreover the VOC needed larger European representation to run its local business and therefore stimulated growt in numbers of an Indo population of Dutch descent. These Indos played important roles as VOC officials. VOC representatives, called residents, at the royal courts were often Indos able to speak the indigenous languages.

Over the centuries of intensive Portuguese and Dutch trade with the islands of the East Indies a relatively large Indo Eurasian population developed. These old Indo families make up the native (Indonesian: Peranakan) stock of Europeans during the ensuing colonial era. Throughout formal colonisation of the Dutch East Indies in the coming century, the majority of registered Europeans were in fact Indo Eurasians.

Note: Oil painting depicting an Indo woman in traditional 'batik sarong kebaya' dress, an originally indigenous aristocratic dress style from the 16th century and commonly worn by Eurasian women well into the 20th century

Indo society during the VOC era

Pre-colonial Indo culture dominated the European segment of society in the East Indies. This culture was heavily Eurasian i.e. hybrid in nature and even the most high ranking Dutch VOC officials were absorbed by it. Indo society was polygot and its' first languages were Malay, Portugis and other creole languages, not Dutch. It was also matriarchal and most Europeans, even the VOC governor-generals would marry into Indo clans. Only by doing so they were able to obtain the necessary connections, patronage, wealth and know how.

"Women based clans absorbed the immigrant males who came without wives. the clan enfolded the newcomer in a network of immigrants with locally born wives, mestizo (Indo) and Asian (Indonesian) kin alike. In the same time the clan eased the adoption of Indies manners for the newcomers." Historian Jean Gelman Taylor in The social world of Batavia, European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia.

The arts and crafts patronized by the Indo elite were usually indigenous e.g. gamelan, batik, various court dances, etc. In their immediate personal habitat they were closely surrounded by indigenous servants. Overall lifestyle was similar to the indigenous elite. Women clothing was often indistinguishable from indigenous fancy dress and many practices were rooted in ancient indigenous court culture.

In an attempt to mitigate cultural dominance of Indo society the expatriate aristocrat baron van Imhoff (1705–1750), VOC governor from 1743 to 1750, founded several institutions to cultivate Dutch culture among the native colonial elite. His Naval Academy for maritime VOC officers in Batavia was exemplary in its' aim to foster western identity. Van Imhoff showed how well he understood the strength of the Indo-Europeans' indigenous derived beliefs and manners when he decreed that even the academy's cooks, stewards and servants were to be European. Another academy decree strictly stipulated: "There shall be no native tongues spoken in the house."

Next governors also vainly tried to introduce the Dutch language in the VOC operated schools and churches, but Portugis and Malay remained the dominant languages. Even the highest VOC officials were unable to pass on their own mother tongue to their offspring. In general the VOC had always recognised the tendency of its servants to be absorbed by the hybrid Indo culture and repeatedly issued regulations limiting higher company positions to men born in the Netherlands.

Indos in colonial history (19th and 20th century)

Indos (short for Indo-Europeans) are a Eurasian people of mixed Indonesian and European descent. The pre-colonial evolution of this hybrid Eurasian community in the East Indies commenced during the arrival of Portuguese traders in the 16th century and continued with the arrival of Dutch traders (VOC) in the 17th and 18th century.

At the break of the 19th century official colonisation of the East Indies started and the territorial claims of the VOC expanded into a fully fledged colony named the Dutch East Indies. The existing pre-colonial Indo-European communities were considerably complimented with Indos descending from European males settling in the Dutch East Indies. These European settlers, who were government officials, business men, planters and particularly military men without wives, engaged into relations with native women. Their offspring was considered Indo-European and if acknowledged by the father belonged to the European legal class in the colony.

In 1860 there were less than 1,000 European females against over 22,000 European males.[1] It was only by the end of the 19th century that a sizeable number of Dutch women started to arrive in the colony.[2] This increasingly hastened the growing pressure to assimilate Indo culture into dominant Dutch culture.[3]

At the end of the colonial era a community of about 300,000 Indo-Europeans was registered as Dutch citizens and Indos continued to form the majority of the European legal class. When in the second half of the 20th century the independent Republic of Indonesia was established, practically all Europeans, including the Indo-Europeans who by now had adopted a one sided identification with their paternal lineage,[4] were expelled from the country.

There are distinctive historical patterns of evolving social and cultural perspectives on Indo-European society and its culture. Throughout the colonial history of the Dutch East Indies key cultural elements such as language, clothing and lifestyle have a different emphasis in each phase of its evolution. Over time the Indo mix culture was forced to adopt more and more Dutch trades and customs. To describe the colonial era it is diligent to differentiate between each distinctive time period in the 19th and 20th century.

The colonial position of Indos

Formal colonisation commenced at the dawn of the 19th century when the Netherlands took possession of all VOC assets. Before that time the VOC was in principle just another trading power among many, establishing trading posts and settlements in strategic places around the archipelago. The Dutch gradually extended their small nation’s sovereignty over most of the islands in the East Indies.[5] The existing VOC trading posts and its European and Eurasian settlements were developed into Dutch ruled enclaves, with its own administration governing both its indigenous and expatriate populations.

The Dutch East Indies were not the typical settler colony founded through massive emigration from the mother countries (such as the USA or Australia) and hardly involved displacement of the indigenous islanders.[6] Neither was it a plantation colony build on the import of slaves (such as Haiti or Jamaica) or a pure trade post colony (such as Singapore or Macau). It was more of an expansion of the existing chain of VOC trading posts. In stead of mass emigration from the homeland, the sizeable indigenous populations, were controlled through effective political manipulation supported by military force. Servitude of the indigenous masses was enabled through a structure of indirect governance, keeping existing indigenous rulers in place[7] and using the Indo Eurasian population as an intermediary buffer. Being one of the smallest nations in the world it was in fact impossible for the Netherlands to even attempt to establish a typical settler colony.

In 1869 British anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace described the colonial governing structure in his book "The Malay Archipelago"[8]:

"The mode of government now adopted in Java is to retain the whole series of native rulers, from the village chief up to princes, who, under the name of Regents, are the heads of districts about the size of a small English county. With each Regent is placed a Dutch Resident, or Assistant Resident, who is considered to be his "elder brother," and whose "orders" take the form of "recommendations," which are, however, implicitly obeyed. Along with each Assistant Resident is a Controller, a kind of inspector of all the lower native rulers, who periodically visits every village in the district, examines the proceedings of the native courts, hears complaints against the head-men or other native chiefs, and superintends the Government plantations."

The need for a sizeable European population to administer the vast region of the East Indies did however initially steer colonial policies to stimulate inter-marriage of European men with native women. Up to the 19th century Indos often occupied the role of 'Resident', 'Assistant Resident' or 'Controleur'.[9] Colonial legislation allowed for assimilation of the relatively large racially mixed Indo population into the European stratosphere of the colonial hierarchy. The official judicial (and racial) division had three layers where the top layer of Europeans in fact included a majority of Indo Europeans. Subsequently these Eurasians were not registered as a separate ethnic group, but were included in the European headcount [10] Unlike other colonies such as South Africa which had a strict policy of ‘Apartheid’ (i.e. stringent racial segregation) and mixed race people were put in the separate legal class of Coloureds.[11]

In comparison to the British Indies and overall colonialism worldwide, strictly speaking the Dutch version of colonial policies and legislation did not maintain a so called colour line.[12] In comparison to Catholic colonial powers there was a lesser degree of missionary zealotry. However it cannot be maintained that the actual expatriate colonists did not share similarly racist values and beliefs along the line of pseudo scientific theories based on proto-social Darwinism, placing the white Caucasian race at the top of society i.e. 'naturally' in charge of dominating and civilizing non white populations. Also in the Dutch East Indies colonial practice was based on these typical values leading to cultural hegemony and chauvinism as seen in colonies around the world. So even though there was in fact no official ‘colour line’ excluding Indo Eurasians, there certainly has always been a ‘shade bar’.[13] What in comparison to other colonial powers of the time sometimes looked like a liberal and even modern attitude towards race mixing, was basically grounded in Dutch pragmatism and opportunism.[14]

The process of colonisation imposed Dutch economical and cultural domination over the resources, labor and markets of the East Indies. It dominated to a high degree its’ organisational and socio-cultural structures and to a lesser degree its’ religious and linguistic structures. The pragmatic and opportunistic colonial policy and cultural perception regarding the Indo Eurasians varied throughout history. But towards the end of the colonial period the Indo-Eurasian mix culture came under exceeding pressure to assimilate completely into Dutch imposed culture.[15]

Indo ethnicity

All Indo families are rooted in the original coalescence between a European forefather and a native born primordial mother.[16] The Indo community as a whole is made out of many different ethnic European and Indonesian combinations and various degrees of racial blending.[17] These combinations include mixes of diverse European peoples such as for example Portuguese, Dutch, Belgian, German, French and British people, with equally diverse Indonesian peoples such as for example Javanese, Sumatran, Moluccan and Minahassa people. But also to a lesser degree Chinese, Indian, Sri-lankan and African people that had settled in the East Indies.[18]

Due to the above described diversity the ethnic features of each Indo family (member) may vary considerably.[19] Notwithstanding their European legal status and even though all family names were uniformly European, their ethnic features made most Indos in colonial times quite easily distinguishable from the full blooded Dutch expatriate or settler and often physically indistinguishable from indigenous islanders. This ethnic diversity also meant that each Indo family (member) may have had an individual perception of identity and racial affiliation. It was only in the last phases of colonisation a Dutch cultural identity was forced onto all Indo-Europeans.[20]

"No longer quietly incorporated into the Mestizo (Indo) sociability of the eclectic (pre-colonial) Indies world, right wing 'totoks' began to view Indos as a fuzzy and troubling social category." Professor Dr. Frances Gouda.[21]

Indo legal and social status

The Dutch East Indies colonial hierarchy initially only had 2 legal classes of citizens: First the European class; second the Indigenous (Dutch: Inlander, Malay: Bumiputra) class.[22] Unlike for instance Singapore no Eurasian sub-class was ever used to register citizens in the Dutch East Indies and Indos were per definition included in the European census.[23]

The authoritative census of 1930 shows 240,162 people belonging to the European legal class of which 208,269 (86,7%) were Dutch nationals. Only 25,8% of the Dutch nationals were expatriate Dutchmen, leaving a vast majority of native born Indo-Europeans. [24] Still the European population of the Dutch East Indies was no more than 0.4% of the total population.

Indos lived in a patriarchal social and legal system. As colonial systems are per definition non-egalitarian for Indo children to obtain the legal status of European (i.e. the highest level of colonial hierarchy) the European father was required to officially acknowledge his children with the indigenous mother.[26] If a European male decided to acknowledge his children he would often marry his indigenous partner to legitimise their relationship[27] This did not always happen and a considerable number of Indo children assimilated into their mothers’ indigenous community. The colonial saying to describe this phenomenon was “The (Indo) child would disappear into the kampung (English: native village)”.[28] Only after the introduction of the 1848 civil code it was allowed for a couple belonging to two different religious groups to marry.[29]

Indo family names

Most Indo families will have European family names, as throughout colonial history the Indo-European community mostly followed patriarchal lines to determine its European roots. Family names are mostly Dutch, but also include many English, French, German and Portuguese family names. Once the total numbers of the community allowed for it Indos would usually marry amongst their own social group and the vast majority of Indo children were born from these marriages.[30] Due to the community’s female surplus Indo women would also marry newly arrived European settlers, as well as indigenous men, who were usually educated Christians that had obtained the so called ‘European equality’ status (Dutch: Gelijkgesteld), following a legal ordinance introduced in 1871.[31]

The civil code of 1848 even stipulated that indigenous men would acquire the European status of their Indo-European wives after marriage. With the arrival of more and more Dutch women [32] in the colony this law suddenly became highly contentious. In the juridical congress of 1878 the ruling was heavily debated as Dutch legal experts did not want European women to “marry into the kampung” and by 1898 this statue was reversed. Another sign pressure on the Eurasian nature of Indo culture was increasing.[33]

Indo women who would marry indigenous men would carry their husband’s family name and their children would be registered according to their father’s ethnicity e.g. Moluccan or Menadonese, but retain his legal class of European Equality status. Notable examples are South Mollucan leaders Chris Soumokil (1905–1966) and Johan Manusama (1910–1995) who both had Indo mothers and were legally classified as European.

Indo society

Notwithstanding Indos officially belonged to the European legal class, colonial society consisted of a very complex structure of many social distinctions. The European segment of society can broadly be divided into the following 3 social layers:

Indo languages

Tjalie Robinson, the author responsible for uplifting the historical and cultural status of the Pecok language. There have been many Indo languages that developed throughout history. Wherever there was considerable inter mixing between Europeans and indigenous islanders distinctive creole languages evolved. The most spoken creole was Pecok and the oldest one Portugis. But other variations such as Javindo also existed. Most languages have died out due to the loss of its function and loss of its speakers. The Pecok mix language reflects the ethnic origin of Indos. Typified as a mixed marriage language, the grammar of Pecok is based on the maternal Malay language and the lexicon on the paternal Dutch language.

At the beginning of colonisation Indos were at least bi-lingual and as off the VOC era Indos have always been used as translators and interpreters of indigenous languages.[35] Their first language was often Malay or a creole language. By the end of the 19th century a research project showed that 70% of (Indo)European children in their first year of elementary school still spoke little to no Dutch.[36]

To persuade his brother in law, the father of Conrad Théodoor van Deventer (who later became the leading spokesman of the 'Ethical Policy'), not to take the position of principal at the 'Koning Willem III' school in Batavia (the only school for secondary education in the Dutch East Indies), newspaper editor Conrad Busken Huet expressed the following popular opinion among the expatriate Dutch community in 1869: "...the Indies climate is fatally detrimental to the proper functioning of their [schoolchildren's] brains, even when born out of pure blooded European parents, you can see the liplap [abusive term for Indos] nature in their faces. Simplistic language forms like Malay seem to eliminate parts of their thinking capabilities, so that education [...] is futile. [...] Even the best among them will remain deficient and will end up to be no more than barely tolerable civil servants." [37]

In the next century of the colonial era creole languages were further discredited and Indos were expected to speak Dutch as their first language.[38] To a degree the use of Malay and Pecok have persisted in private conversation and literature. Only through the post colonial work of Indo author Tjalie Robinson the Pecok language regained its' cultural status.[39]

At the break of the 19th century official colonisation of the East Indies started and the territorial claims of the VOC expanded into a fully fledged colony named the Dutch East Indies. The existing pre-colonial Indo-European communities were considerably complimented with Indos descending from European males settling in the Dutch East Indies. These European settlers, who were government officials, business men, planters and particularly military men without wives, engaged into relations with native women. Their offspring was considered Indo-European and if acknowledged by the father belonged to the European legal class in the colony.

In 1860 there were less than 1,000 European females against over 22,000 European males.[1] It was only by the end of the 19th century that a sizeable number of Dutch women started to arrive in the colony.[2] This increasingly hastened the growing pressure to assimilate Indo culture into dominant Dutch culture.[3]

At the end of the colonial era a community of about 300,000 Indo-Europeans was registered as Dutch citizens and Indos continued to form the majority of the European legal class. When in the second half of the 20th century the independent Republic of Indonesia was established, practically all Europeans, including the Indo-Europeans who by now had adopted a one sided identification with their paternal lineage,[4] were expelled from the country.

There are distinctive historical patterns of evolving social and cultural perspectives on Indo-European society and its culture. Throughout the colonial history of the Dutch East Indies key cultural elements such as language, clothing and lifestyle have a different emphasis in each phase of its evolution. Over time the Indo mix culture was forced to adopt more and more Dutch trades and customs. To describe the colonial era it is diligent to differentiate between each distinctive time period in the 19th and 20th century.

The colonial position of Indos

Formal colonisation commenced at the dawn of the 19th century when the Netherlands took possession of all VOC assets. Before that time the VOC was in principle just another trading power among many, establishing trading posts and settlements in strategic places around the archipelago. The Dutch gradually extended their small nation’s sovereignty over most of the islands in the East Indies.[5] The existing VOC trading posts and its European and Eurasian settlements were developed into Dutch ruled enclaves, with its own administration governing both its indigenous and expatriate populations.

The Dutch East Indies were not the typical settler colony founded through massive emigration from the mother countries (such as the USA or Australia) and hardly involved displacement of the indigenous islanders.[6] Neither was it a plantation colony build on the import of slaves (such as Haiti or Jamaica) or a pure trade post colony (such as Singapore or Macau). It was more of an expansion of the existing chain of VOC trading posts. In stead of mass emigration from the homeland, the sizeable indigenous populations, were controlled through effective political manipulation supported by military force. Servitude of the indigenous masses was enabled through a structure of indirect governance, keeping existing indigenous rulers in place[7] and using the Indo Eurasian population as an intermediary buffer. Being one of the smallest nations in the world it was in fact impossible for the Netherlands to even attempt to establish a typical settler colony.

In 1869 British anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace described the colonial governing structure in his book "The Malay Archipelago"[8]:

"The mode of government now adopted in Java is to retain the whole series of native rulers, from the village chief up to princes, who, under the name of Regents, are the heads of districts about the size of a small English county. With each Regent is placed a Dutch Resident, or Assistant Resident, who is considered to be his "elder brother," and whose "orders" take the form of "recommendations," which are, however, implicitly obeyed. Along with each Assistant Resident is a Controller, a kind of inspector of all the lower native rulers, who periodically visits every village in the district, examines the proceedings of the native courts, hears complaints against the head-men or other native chiefs, and superintends the Government plantations."

The need for a sizeable European population to administer the vast region of the East Indies did however initially steer colonial policies to stimulate inter-marriage of European men with native women. Up to the 19th century Indos often occupied the role of 'Resident', 'Assistant Resident' or 'Controleur'.[9] Colonial legislation allowed for assimilation of the relatively large racially mixed Indo population into the European stratosphere of the colonial hierarchy. The official judicial (and racial) division had three layers where the top layer of Europeans in fact included a majority of Indo Europeans. Subsequently these Eurasians were not registered as a separate ethnic group, but were included in the European headcount [10] Unlike other colonies such as South Africa which had a strict policy of ‘Apartheid’ (i.e. stringent racial segregation) and mixed race people were put in the separate legal class of Coloureds.[11]

In comparison to the British Indies and overall colonialism worldwide, strictly speaking the Dutch version of colonial policies and legislation did not maintain a so called colour line.[12] In comparison to Catholic colonial powers there was a lesser degree of missionary zealotry. However it cannot be maintained that the actual expatriate colonists did not share similarly racist values and beliefs along the line of pseudo scientific theories based on proto-social Darwinism, placing the white Caucasian race at the top of society i.e. 'naturally' in charge of dominating and civilizing non white populations. Also in the Dutch East Indies colonial practice was based on these typical values leading to cultural hegemony and chauvinism as seen in colonies around the world. So even though there was in fact no official ‘colour line’ excluding Indo Eurasians, there certainly has always been a ‘shade bar’.[13] What in comparison to other colonial powers of the time sometimes looked like a liberal and even modern attitude towards race mixing, was basically grounded in Dutch pragmatism and opportunism.[14]

The process of colonisation imposed Dutch economical and cultural domination over the resources, labor and markets of the East Indies. It dominated to a high degree its’ organisational and socio-cultural structures and to a lesser degree its’ religious and linguistic structures. The pragmatic and opportunistic colonial policy and cultural perception regarding the Indo Eurasians varied throughout history. But towards the end of the colonial period the Indo-Eurasian mix culture came under exceeding pressure to assimilate completely into Dutch imposed culture.[15]

Indo ethnicity

All Indo families are rooted in the original coalescence between a European forefather and a native born primordial mother.[16] The Indo community as a whole is made out of many different ethnic European and Indonesian combinations and various degrees of racial blending.[17] These combinations include mixes of diverse European peoples such as for example Portuguese, Dutch, Belgian, German, French and British people, with equally diverse Indonesian peoples such as for example Javanese, Sumatran, Moluccan and Minahassa people. But also to a lesser degree Chinese, Indian, Sri-lankan and African people that had settled in the East Indies.[18]

Due to the above described diversity the ethnic features of each Indo family (member) may vary considerably.[19] Notwithstanding their European legal status and even though all family names were uniformly European, their ethnic features made most Indos in colonial times quite easily distinguishable from the full blooded Dutch expatriate or settler and often physically indistinguishable from indigenous islanders. This ethnic diversity also meant that each Indo family (member) may have had an individual perception of identity and racial affiliation. It was only in the last phases of colonisation a Dutch cultural identity was forced onto all Indo-Europeans.[20]

"No longer quietly incorporated into the Mestizo (Indo) sociability of the eclectic (pre-colonial) Indies world, right wing 'totoks' began to view Indos as a fuzzy and troubling social category." Professor Dr. Frances Gouda.[21]

Indo legal and social status

The Dutch East Indies colonial hierarchy initially only had 2 legal classes of citizens: First the European class; second the Indigenous (Dutch: Inlander, Malay: Bumiputra) class.[22] Unlike for instance Singapore no Eurasian sub-class was ever used to register citizens in the Dutch East Indies and Indos were per definition included in the European census.[23]

The authoritative census of 1930 shows 240,162 people belonging to the European legal class of which 208,269 (86,7%) were Dutch nationals. Only 25,8% of the Dutch nationals were expatriate Dutchmen, leaving a vast majority of native born Indo-Europeans. [24] Still the European population of the Dutch East Indies was no more than 0.4% of the total population.

Indos lived in a patriarchal social and legal system. As colonial systems are per definition non-egalitarian for Indo children to obtain the legal status of European (i.e. the highest level of colonial hierarchy) the European father was required to officially acknowledge his children with the indigenous mother.[26] If a European male decided to acknowledge his children he would often marry his indigenous partner to legitimise their relationship[27] This did not always happen and a considerable number of Indo children assimilated into their mothers’ indigenous community. The colonial saying to describe this phenomenon was “The (Indo) child would disappear into the kampung (English: native village)”.[28] Only after the introduction of the 1848 civil code it was allowed for a couple belonging to two different religious groups to marry.[29]

Indo family names

Most Indo families will have European family names, as throughout colonial history the Indo-European community mostly followed patriarchal lines to determine its European roots. Family names are mostly Dutch, but also include many English, French, German and Portuguese family names. Once the total numbers of the community allowed for it Indos would usually marry amongst their own social group and the vast majority of Indo children were born from these marriages.[30] Due to the community’s female surplus Indo women would also marry newly arrived European settlers, as well as indigenous men, who were usually educated Christians that had obtained the so called ‘European equality’ status (Dutch: Gelijkgesteld), following a legal ordinance introduced in 1871.[31]

The civil code of 1848 even stipulated that indigenous men would acquire the European status of their Indo-European wives after marriage. With the arrival of more and more Dutch women [32] in the colony this law suddenly became highly contentious. In the juridical congress of 1878 the ruling was heavily debated as Dutch legal experts did not want European women to “marry into the kampung” and by 1898 this statue was reversed. Another sign pressure on the Eurasian nature of Indo culture was increasing.[33]

Indo women who would marry indigenous men would carry their husband’s family name and their children would be registered according to their father’s ethnicity e.g. Moluccan or Menadonese, but retain his legal class of European Equality status. Notable examples are South Mollucan leaders Chris Soumokil (1905–1966) and Johan Manusama (1910–1995) who both had Indo mothers and were legally classified as European.

Indo society

Notwithstanding Indos officially belonged to the European legal class, colonial society consisted of a very complex structure of many social distinctions. The European segment of society can broadly be divided into the following 3 social layers:

- 1) a small upper class layer of colonial and commercial leadership, including governors, directors, ceo's, business managers, generals, etc. Mostly, but not solely consisting of expatriate Dutchmen;

- 2) a large middle class of mostly Indo civil servants, making up the backbone of all officialdom;

- 3) lower income (to poor) layer, solely consisting of Indos that were legally European, but had a living standard close or similar to the indigenous masses. Indo people in the third layer were affectionately called the 'Kleine bung', a mixed Dutch-Malay language term translated to 'Little brother'.

Indo languages

Tjalie Robinson, the author responsible for uplifting the historical and cultural status of the Pecok language. There have been many Indo languages that developed throughout history. Wherever there was considerable inter mixing between Europeans and indigenous islanders distinctive creole languages evolved. The most spoken creole was Pecok and the oldest one Portugis. But other variations such as Javindo also existed. Most languages have died out due to the loss of its function and loss of its speakers. The Pecok mix language reflects the ethnic origin of Indos. Typified as a mixed marriage language, the grammar of Pecok is based on the maternal Malay language and the lexicon on the paternal Dutch language.

At the beginning of colonisation Indos were at least bi-lingual and as off the VOC era Indos have always been used as translators and interpreters of indigenous languages.[35] Their first language was often Malay or a creole language. By the end of the 19th century a research project showed that 70% of (Indo)European children in their first year of elementary school still spoke little to no Dutch.[36]

To persuade his brother in law, the father of Conrad Théodoor van Deventer (who later became the leading spokesman of the 'Ethical Policy'), not to take the position of principal at the 'Koning Willem III' school in Batavia (the only school for secondary education in the Dutch East Indies), newspaper editor Conrad Busken Huet expressed the following popular opinion among the expatriate Dutch community in 1869: "...the Indies climate is fatally detrimental to the proper functioning of their [schoolchildren's] brains, even when born out of pure blooded European parents, you can see the liplap [abusive term for Indos] nature in their faces. Simplistic language forms like Malay seem to eliminate parts of their thinking capabilities, so that education [...] is futile. [...] Even the best among them will remain deficient and will end up to be no more than barely tolerable civil servants." [37]

In the next century of the colonial era creole languages were further discredited and Indos were expected to speak Dutch as their first language.[38] To a degree the use of Malay and Pecok have persisted in private conversation and literature. Only through the post colonial work of Indo author Tjalie Robinson the Pecok language regained its' cultural status.[39]

Historic overview colonial era (1800-1900)

19th century

During the first half of formal colonisation many practices the VOC had introduced in the previous centuries remained in place, and the overall levels of independence from the mother country remained equally high. The position of Indos as important trading intermediaries and main local representation of Dutch governance also remained the same.[40] Moreover European society in the East Indies was in fact dominated by Indo culture and customs that determined a.o. the lifestyle, language and dress code of its’ European population. European new arrivals settling in the East Indies adopted many of the Indo customs.[41]

In the 1830s colonial policies steered from the Netherlands (Ministry of colonial affairs) to decrease the autonomous and arbitrary nature of the colony, considerably increased pressure on the Indo population to ‘Dutchify’ its’ society.[40] Particularly during the implementation of the 'Cultivation System' legislation and regulations discriminatory against Indos were enforced. When the 'Cultivation System' policy was abandoned in 1870 it however also put in place a ban for Indos to own land.[42] Under threat of marginalisation the Indo community was forced to reflect on its position in the Dutch East Indies. For the first time in history Indos began to organise politically in an attempt to emancipate as a group.

Meanwhile the number of Indos in the 19th century also increased as the existing pre-colonial communities were complimented with offspring of European military men and indigenous women.

French and British interregnum (1806-1816)

A few years into formal colonisation of the East Indies, in Europe the Dutch Republic was occupied by the French forces of Napoleon. This resulted in an influx of French settlers in the East Indies. Notwithstanding the fact that the Dutch government went into exile in England and formally ceded its colonial possessions to Great Britain, the pro-French Governor General of the Dutch East Indies fought the British before surrendering the colony.[43] He was replaced by the British Governor Raffles, who later founded the city of Singapore. The 10 years of the French-British interregnum (1806–1816) saw an influx of British settlers in the East Indies. To this day one can still find many French and British family names in the Indo community.[44]

At the time the British took over governmental responsibilities of the Dutch East Indies, the European segment of society was still strongly Eurasian in nature. Even most Dutch governor-generals had married into matriarchal Indo clans and the European segment of society was in fact dominated by Indo culture. The polygot society he encountered spoke Malay, Portugis and other creole languages, as its first language and Dutch or other European languages only as a second or third language. The arts and crafts patronized by the Indo elite were usually indigenous e.g. gamelan, batik, various court dances, etc. Women clothing was often indistinguishable from indigenous fancy dress and many practices were rooted in ancient indigenous court culture.[45]

Intending to modernize the colony Raffles, a keen anthropologist and progressive administrator, attempted to westernize the character of the Dutch, Indo and Indigenous colonial elite alike. He was the first European governor to establish western style schooling and institutions[46] and by show of example attempted to introduce western values and morals.[47]

This first all encompassing attack on the existing Indo character of European society also revealed its political and cultural strength and the British were in the end unable to drastically change it. Only in later decennia with the arrival of larger numbers of Dutch expatriates, that included women and families, Indo dominance would be broken.[48]

Indos in the Colonial Army (1817-1900)

After the defeat of Napoleon and the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 colonial government of the East Indies was ceded back to the Dutch in 1817. To secure unchallenged dominion over its colony in the East Indies the Dutch started to consolidate its power base through military campaigns ensuring the Dutch tricolor was firmly planted in all corners of the Archipelago. These military campaigns included: the Padri War (1821–1837), the Java War (1825–1830) and the Aceh War (1873–1904). This raised the need for a considerable military build up of the colonial army (KNIL). From all over Europe soldiers were recruited to join the KNIL.[49]

This new wave of Indo Eurasian families compounded to the already plural nature of the Indo community as this time it specifically concerned soldiers raising families on military compounds. Children born from the European KNIL soldiers and indigenous women [50] were immediately acknowledged as Europeans as it was more cost effective to recruit European soldiers locally than in Europe.

The colonial army became the largest employer in the Dutch East Indies and Indo males born into barrack life, also joined the KNIL. From the age of 7 Indo boys were sent to military school and at the age of 18, with the lack of other career opportunities, joined the KNIL.[51] At large Indos chose to join the non combatant units of the colonial army. The period up to 1870 showed the highest number of professional Indo soldiers.

After 1870 the number of Indos that enlisted in the colonial army strongly declined, as other career opportunities in the emerging agricultural industries presented themselves and the ongoing colonial wars continued. The unwillingness to join the colonial army forced the government to re-focus on military recruitment in Europe, which in turn resulted in a second big wave of Indo families based in KNIL induced migration during the 30 years of the Aceh War.[52]

Indos and the Cultivation System (1830-1870)

Once the island of Java, the centre of the colony, was ‘pacified’ after the defeat of Prince Diponogoro in 1830, the Dutch implemented a policy called the ‘Cultuurstelsel’ (English: Cultivation system). Along with its implementation Baron Jean Chrétien Baud, Governor-General (1833–1836) and Minister of Colonies (1840–1848), added discrimatory regulations aimed to withhold Indos from key governamental functions. He was of the opinion that full blooded i.e. white Dutch officials were better suited to persuade native nobility to comply to the ‘Cultivation System’. His thinking, influenced by his aristocratic background, was a radical shift from the opinion that Indos were the ideal intermediaries towards the indigenous rulers.[53]

Indo Residents[54] were removed from their positions as liaisons to the Javanese and Madurese Regents,[55] a role they had played since the VOC era. To further complicate the appointment and promotion of Indos, Baud enforced a Royal decree stipulating that governamental functions could only be granted on request of the Governor-General and needed approval by the Dutch King himself. Additionally in 1837 the pensions of Indo civil servants was cut in half. The reasoning behind that was the conviction that native born Indo officials should be easily able to adhere to lower living standards than expatriate Dutch officials born in the Netherlands.[56]

Another discrimatory measure stipulated that it was mandatory for colonial government officials to be educated in the Netherlands.[57] Simultaneously the already limited educational opportunities for the native born people of the Dutch East Indies (European, Indo-European and Indigenous alike) further decreased. All these restrictions had a direct impact on the livelihood of the Indo community, which finally resulted in revolutionary tensions.

In 1848 the leading figures of the colonial capital Batavia (Now Jakarta) assembled in protest. In fear of a violent backlash from the populous Indo community in Batavia the Governor-General at the time ordered the army to the highest state of preparedness.[58] Violence was averted, but 1848 was a watershed moment starting the political emancipation of Indos, which in the next century would result in several Indo dominated political parties of which some even advocated independence from the Netherlands.

Cautious not to alianate the largest segment of European society the second half of 19th century saw a change in colonial policy and loosening of the discrimatory measures against Indos. Opportunities for local education also increased a little.[59] Towards the end of the century the 'Cultivation System' was abandoned however pressure on the Indo community continued with arguments raising the question how native born Indo-Europeans could ever truly represent Western civilisation.[60]

During the first half of formal colonisation many practices the VOC had introduced in the previous centuries remained in place, and the overall levels of independence from the mother country remained equally high. The position of Indos as important trading intermediaries and main local representation of Dutch governance also remained the same.[40] Moreover European society in the East Indies was in fact dominated by Indo culture and customs that determined a.o. the lifestyle, language and dress code of its’ European population. European new arrivals settling in the East Indies adopted many of the Indo customs.[41]

In the 1830s colonial policies steered from the Netherlands (Ministry of colonial affairs) to decrease the autonomous and arbitrary nature of the colony, considerably increased pressure on the Indo population to ‘Dutchify’ its’ society.[40] Particularly during the implementation of the 'Cultivation System' legislation and regulations discriminatory against Indos were enforced. When the 'Cultivation System' policy was abandoned in 1870 it however also put in place a ban for Indos to own land.[42] Under threat of marginalisation the Indo community was forced to reflect on its position in the Dutch East Indies. For the first time in history Indos began to organise politically in an attempt to emancipate as a group.

Meanwhile the number of Indos in the 19th century also increased as the existing pre-colonial communities were complimented with offspring of European military men and indigenous women.

French and British interregnum (1806-1816)

A few years into formal colonisation of the East Indies, in Europe the Dutch Republic was occupied by the French forces of Napoleon. This resulted in an influx of French settlers in the East Indies. Notwithstanding the fact that the Dutch government went into exile in England and formally ceded its colonial possessions to Great Britain, the pro-French Governor General of the Dutch East Indies fought the British before surrendering the colony.[43] He was replaced by the British Governor Raffles, who later founded the city of Singapore. The 10 years of the French-British interregnum (1806–1816) saw an influx of British settlers in the East Indies. To this day one can still find many French and British family names in the Indo community.[44]

At the time the British took over governmental responsibilities of the Dutch East Indies, the European segment of society was still strongly Eurasian in nature. Even most Dutch governor-generals had married into matriarchal Indo clans and the European segment of society was in fact dominated by Indo culture. The polygot society he encountered spoke Malay, Portugis and other creole languages, as its first language and Dutch or other European languages only as a second or third language. The arts and crafts patronized by the Indo elite were usually indigenous e.g. gamelan, batik, various court dances, etc. Women clothing was often indistinguishable from indigenous fancy dress and many practices were rooted in ancient indigenous court culture.[45]

Intending to modernize the colony Raffles, a keen anthropologist and progressive administrator, attempted to westernize the character of the Dutch, Indo and Indigenous colonial elite alike. He was the first European governor to establish western style schooling and institutions[46] and by show of example attempted to introduce western values and morals.[47]

This first all encompassing attack on the existing Indo character of European society also revealed its political and cultural strength and the British were in the end unable to drastically change it. Only in later decennia with the arrival of larger numbers of Dutch expatriates, that included women and families, Indo dominance would be broken.[48]

Indos in the Colonial Army (1817-1900)

After the defeat of Napoleon and the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 colonial government of the East Indies was ceded back to the Dutch in 1817. To secure unchallenged dominion over its colony in the East Indies the Dutch started to consolidate its power base through military campaigns ensuring the Dutch tricolor was firmly planted in all corners of the Archipelago. These military campaigns included: the Padri War (1821–1837), the Java War (1825–1830) and the Aceh War (1873–1904). This raised the need for a considerable military build up of the colonial army (KNIL). From all over Europe soldiers were recruited to join the KNIL.[49]

This new wave of Indo Eurasian families compounded to the already plural nature of the Indo community as this time it specifically concerned soldiers raising families on military compounds. Children born from the European KNIL soldiers and indigenous women [50] were immediately acknowledged as Europeans as it was more cost effective to recruit European soldiers locally than in Europe.

The colonial army became the largest employer in the Dutch East Indies and Indo males born into barrack life, also joined the KNIL. From the age of 7 Indo boys were sent to military school and at the age of 18, with the lack of other career opportunities, joined the KNIL.[51] At large Indos chose to join the non combatant units of the colonial army. The period up to 1870 showed the highest number of professional Indo soldiers.

After 1870 the number of Indos that enlisted in the colonial army strongly declined, as other career opportunities in the emerging agricultural industries presented themselves and the ongoing colonial wars continued. The unwillingness to join the colonial army forced the government to re-focus on military recruitment in Europe, which in turn resulted in a second big wave of Indo families based in KNIL induced migration during the 30 years of the Aceh War.[52]

Indos and the Cultivation System (1830-1870)

Once the island of Java, the centre of the colony, was ‘pacified’ after the defeat of Prince Diponogoro in 1830, the Dutch implemented a policy called the ‘Cultuurstelsel’ (English: Cultivation system). Along with its implementation Baron Jean Chrétien Baud, Governor-General (1833–1836) and Minister of Colonies (1840–1848), added discrimatory regulations aimed to withhold Indos from key governamental functions. He was of the opinion that full blooded i.e. white Dutch officials were better suited to persuade native nobility to comply to the ‘Cultivation System’. His thinking, influenced by his aristocratic background, was a radical shift from the opinion that Indos were the ideal intermediaries towards the indigenous rulers.[53]

Indo Residents[54] were removed from their positions as liaisons to the Javanese and Madurese Regents,[55] a role they had played since the VOC era. To further complicate the appointment and promotion of Indos, Baud enforced a Royal decree stipulating that governamental functions could only be granted on request of the Governor-General and needed approval by the Dutch King himself. Additionally in 1837 the pensions of Indo civil servants was cut in half. The reasoning behind that was the conviction that native born Indo officials should be easily able to adhere to lower living standards than expatriate Dutch officials born in the Netherlands.[56]

Another discrimatory measure stipulated that it was mandatory for colonial government officials to be educated in the Netherlands.[57] Simultaneously the already limited educational opportunities for the native born people of the Dutch East Indies (European, Indo-European and Indigenous alike) further decreased. All these restrictions had a direct impact on the livelihood of the Indo community, which finally resulted in revolutionary tensions.

In 1848 the leading figures of the colonial capital Batavia (Now Jakarta) assembled in protest. In fear of a violent backlash from the populous Indo community in Batavia the Governor-General at the time ordered the army to the highest state of preparedness.[58] Violence was averted, but 1848 was a watershed moment starting the political emancipation of Indos, which in the next century would result in several Indo dominated political parties of which some even advocated independence from the Netherlands.

Cautious not to alianate the largest segment of European society the second half of 19th century saw a change in colonial policy and loosening of the discrimatory measures against Indos. Opportunities for local education also increased a little.[59] Towards the end of the century the 'Cultivation System' was abandoned however pressure on the Indo community continued with arguments raising the question how native born Indo-Europeans could ever truly represent Western civilisation.[60]

Historic overview colonial era (1900-1963)

20th century

In the next century Dutch ethnocentric beliefs dominated the administration's politics and policies. In an effort to legitimize and promote the colonial system the so called ‘Ethical Policy’ was developed and implemented (1900–1930), while at the same time the superiority syndrome (i.e. The White Man's Burden) prevailed more than ever. Also on a social level the arrival of larger number of Dutch expatriates, for the first time including many Dutch women and families, continued to affect the nature of Indo-European society. In the end political and social ‘Dutchification’ almost totally eradicated the Eurasian character of Indo culture.

The process of political emancipation of Indos, which started in the previous century, continued resulting in various political organisations such as Dekker‘s ‘Indische Party’ and Zaalberg’s 'Indo European Alliance', but was cut short by WWII and never established a structural connection to the Indonesian independence movement.

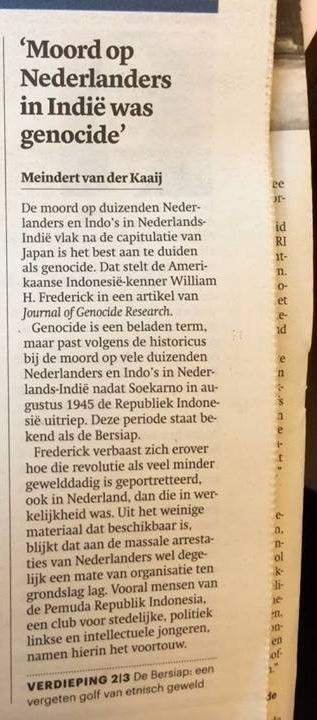

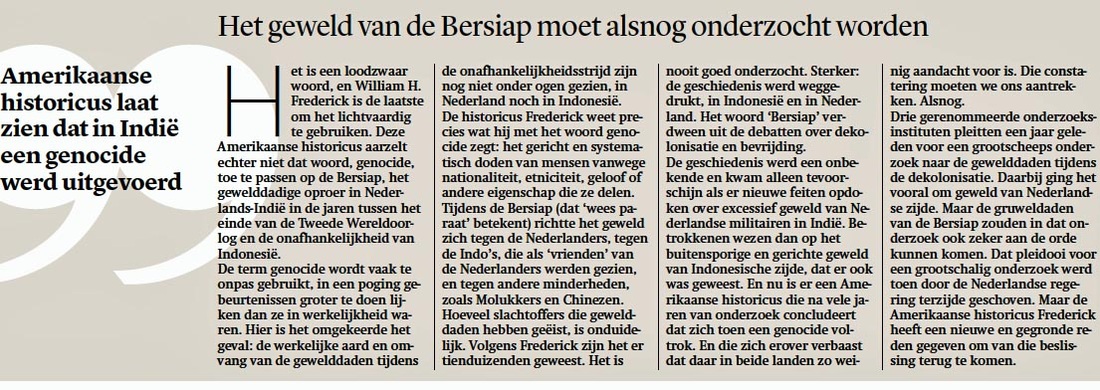

Execution of POW in New Guinea, 24 October 1943. When World War II broke out the Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940, while the Dutch East Indies was occupied by Imperial Japan in 1942. All non Axis Europeans, including most Indo-European males, were interned in Japanese prisoner camps until 1945. During this period close to 25% of the POW’s did not survive their imprisonment.[61][62]

The end of WWII heralded the end of colonialsm worldwide. From 1945 to 1949 the Indonesian National Revolution turned the former Dutch East Indies into an increasingly hostile environment for Indo-Europeans. Violence aimed towards Indo-Europeans during its early Bersiap period (1945-1946) accumulated in almost 20,000 deaths.[63]

In 1949 the Dutch recognised the Republic of Indonesia, save the area of Dutch New Guinea. Most Indos that chose Indonesian citizenship retracted their decision due to continued anti-Dutch sentiments and regulations.[64] Many Indo Europeans also hoped for a future in Dutch New Guinea until in 1962-1963 this area too was annexed into present day Indonesia, officially ending the colonial era of the Dutch East Indies.

The Indo diaspora which started in the ‘Bersiap’ period continued up to 1964 and resulted in the emigration of practically all Indo-Europeans from a turbulent young Indonesian nation.

Indos in the Colonial Army (1900-1942)

In the first 10 years of the 20th century there was a last push to dominate all corners of the Dutch East Indies. Military campaigns by the expedient and infamous Van Heutsz , who had been made Governor-General (1904-1909) for his victory in the Aceh War (1904), subdued the last indigenous resistance in Bali (1906 and 1908) and Papua, bringing the whole of the Dutch East Indies under direct colonial rule. Meanwhile the number of Indos signing up to join the colonial army (KNIL) was at an all time low.[65]

Notwithstanding the large numbers of Indo offspring (known as ‘Anak Kolong’) from the 2 main waves of KNIL induced migration in the previous century, the number of professional Indo soldiers kept declining steadily. At the turn of the century all schools for officers in the Dutch East Indies had been liquidated leaving military career opportunities limited to the rank of non-commissioned officers. Officers were now solely educated and recruited in the Netherlands. Meanwhile civilian career opportunities increased and even Indo boys born into barrack life preferred seeking employment outside the army.[66]

In 1910 only 5 Indo-Europeans volunteered for military service, while there was a shortage of 15,310 European soldiers. As a result the KNIL remained dependent on lengthy and costly recruitment in Europe and was forced to re-organise its internal structure. Ethnic Ambonese were considered the most competent and reliable indigenous soldiers and their military status was practically equalised to European status. In the following years slots for Ambonese i.e. South Moluccan KNIL soldiers also greatly increased to compensate for the lack of Indo-Europeans.[67]

Most KNIL soldiers and non commissioned officers now consisted of indigenous people. The vast majority of indigenous soldiers were ethnic Javanese. While a relatively high percentage was from the Minahasa and the South Moluccas. To ensure a sizeable European military segment and enforce the return of Indos to the KNIL the colonial government introduced obligatory military service for the (Indo-)European population of the Dutch East Indies in 1917.[68]

The introduction of mandatory military service for (Indo-) European conscripts successfully boosted the European segment in the colonial army, while simultaneously reducing costly recruitment in Europe. In 1922 a supplemental legal enactment introduced the creation of a ‘Home guard’ (Dutch: Landstorm) for (Indo-)European conscripts older than 32. By 1940 these legal measures had successfully mitigated the strong trend of Indos discarting the colonial armed forces and had once again secured the proportionally high ratio of 1 European soldier for every 3 Indigenous soldiers.[69]

In the next century Dutch ethnocentric beliefs dominated the administration's politics and policies. In an effort to legitimize and promote the colonial system the so called ‘Ethical Policy’ was developed and implemented (1900–1930), while at the same time the superiority syndrome (i.e. The White Man's Burden) prevailed more than ever. Also on a social level the arrival of larger number of Dutch expatriates, for the first time including many Dutch women and families, continued to affect the nature of Indo-European society. In the end political and social ‘Dutchification’ almost totally eradicated the Eurasian character of Indo culture.

The process of political emancipation of Indos, which started in the previous century, continued resulting in various political organisations such as Dekker‘s ‘Indische Party’ and Zaalberg’s 'Indo European Alliance', but was cut short by WWII and never established a structural connection to the Indonesian independence movement.

Execution of POW in New Guinea, 24 October 1943. When World War II broke out the Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940, while the Dutch East Indies was occupied by Imperial Japan in 1942. All non Axis Europeans, including most Indo-European males, were interned in Japanese prisoner camps until 1945. During this period close to 25% of the POW’s did not survive their imprisonment.[61][62]

The end of WWII heralded the end of colonialsm worldwide. From 1945 to 1949 the Indonesian National Revolution turned the former Dutch East Indies into an increasingly hostile environment for Indo-Europeans. Violence aimed towards Indo-Europeans during its early Bersiap period (1945-1946) accumulated in almost 20,000 deaths.[63]

In 1949 the Dutch recognised the Republic of Indonesia, save the area of Dutch New Guinea. Most Indos that chose Indonesian citizenship retracted their decision due to continued anti-Dutch sentiments and regulations.[64] Many Indo Europeans also hoped for a future in Dutch New Guinea until in 1962-1963 this area too was annexed into present day Indonesia, officially ending the colonial era of the Dutch East Indies.

The Indo diaspora which started in the ‘Bersiap’ period continued up to 1964 and resulted in the emigration of practically all Indo-Europeans from a turbulent young Indonesian nation.

Indos in the Colonial Army (1900-1942)

In the first 10 years of the 20th century there was a last push to dominate all corners of the Dutch East Indies. Military campaigns by the expedient and infamous Van Heutsz , who had been made Governor-General (1904-1909) for his victory in the Aceh War (1904), subdued the last indigenous resistance in Bali (1906 and 1908) and Papua, bringing the whole of the Dutch East Indies under direct colonial rule. Meanwhile the number of Indos signing up to join the colonial army (KNIL) was at an all time low.[65]

Notwithstanding the large numbers of Indo offspring (known as ‘Anak Kolong’) from the 2 main waves of KNIL induced migration in the previous century, the number of professional Indo soldiers kept declining steadily. At the turn of the century all schools for officers in the Dutch East Indies had been liquidated leaving military career opportunities limited to the rank of non-commissioned officers. Officers were now solely educated and recruited in the Netherlands. Meanwhile civilian career opportunities increased and even Indo boys born into barrack life preferred seeking employment outside the army.[66]

In 1910 only 5 Indo-Europeans volunteered for military service, while there was a shortage of 15,310 European soldiers. As a result the KNIL remained dependent on lengthy and costly recruitment in Europe and was forced to re-organise its internal structure. Ethnic Ambonese were considered the most competent and reliable indigenous soldiers and their military status was practically equalised to European status. In the following years slots for Ambonese i.e. South Moluccan KNIL soldiers also greatly increased to compensate for the lack of Indo-Europeans.[67]

Most KNIL soldiers and non commissioned officers now consisted of indigenous people. The vast majority of indigenous soldiers were ethnic Javanese. While a relatively high percentage was from the Minahasa and the South Moluccas. To ensure a sizeable European military segment and enforce the return of Indos to the KNIL the colonial government introduced obligatory military service for the (Indo-)European population of the Dutch East Indies in 1917.[68]

The introduction of mandatory military service for (Indo-) European conscripts successfully boosted the European segment in the colonial army, while simultaneously reducing costly recruitment in Europe. In 1922 a supplemental legal enactment introduced the creation of a ‘Home guard’ (Dutch: Landstorm) for (Indo-)European conscripts older than 32. By 1940 these legal measures had successfully mitigated the strong trend of Indos discarting the colonial armed forces and had once again secured the proportionally high ratio of 1 European soldier for every 3 Indigenous soldiers.[69]

References

Notes & citations

- ^ Van Nimwegen, Nico De demografische geschiedenis van Indische Nederlanders, Report no.64 (Publisher: NIDI, The Hague, 2002) P.18 ISBN 0922 7210 [1]

- ^ Note: The numbers of Dutch females had already increased from 4,000 in 1905 to about 26,000 in 1930. See: Wiseman, Roger. 'Assimilation Out.', (Conference paper, ASAA 2000, Melbourne University.)