"Knowledge of history is the prerequisite to understanding the now and seeing the future."

Pre-colonial history (16th, 17th and 18th century)

Portuguese and Spanish roots (16th century)

The earliest significant presence of Europeans in South East Asia was made out of Portuguese and Spanish traders. Portuguese explorers discovered two trade routes to Asia, sailing around the south of Africa, as well as sailing around the south of America creating a commercial monopoly. In the early 16th century the Portuguese established important trade posts in South East Asia, which was a diverse collection of many rival kingdoms, sultanates and tribes spread over a huge territory of peninsulas and islands. One of the main Portuguese strongholds was located in the so called Spice Islands i.e. the Moluccas. Similarly the Spanish established a dominant presence further north in the Philippines. These historical developments helped build a foundation for large Eurasian communities in this region. Old Eurasian families in the Philippines mainly descend from the Spanish. While the oldest Indo families descend from Portuguese traders and explorers, some family names of old Indo families include Simao, De Fretes, Perera, Henriques, etc

Dutch and English roots (17th and 18th century)

With the decline of the Portuguese and Spanish global empires after the beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch and English maritime merchants started establishing an equally comprehensive global network of trading posts. In 1602 the Dutch founded the first ever joint stock multinational firm, called the United East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC). The VOC’s main aim was to generate profit from international trade with South and South East Asia, also known then and later as the East Indies. The VOC established a dominant European presence on for example the island of Java, as well as on numerous islands north and east of Java. Their English counterparts did the same west of Java in Singapore and Malaya.

Originally, most Dutch VOC employees were traders, accountants, sailors and adventurers and may have thought of themselves as temporary sojourners. British and other Europeans also settled there, usually as traders or professionals. Most of the settlers in the 18th and early 19th centuries were men, without wives. Considerable mixing occurred with the local inhabitants. The VOC and later the colonial government to a certain extent encouraged this, partly to maintain their control over the region. The existing Indo (or Mestizo) population of Portuguese descent was therefore welcome to integrate. A relatively large Indo-European society started to develop in the East Indies. Although most of its members became Dutch citizens, in offset their culture was strongly Eurasian in nature, with equal focus on both the native Asian and foreign European heritage. In fact 'European' society in the Indies was dominated by this Indo culture into which non native born European settlers integrated. This would change coming the formal colonization by the Dutch in the 19th century.

The earliest significant presence of Europeans in South East Asia was made out of Portuguese and Spanish traders. Portuguese explorers discovered two trade routes to Asia, sailing around the south of Africa, as well as sailing around the south of America creating a commercial monopoly. In the early 16th century the Portuguese established important trade posts in South East Asia, which was a diverse collection of many rival kingdoms, sultanates and tribes spread over a huge territory of peninsulas and islands. One of the main Portuguese strongholds was located in the so called Spice Islands i.e. the Moluccas. Similarly the Spanish established a dominant presence further north in the Philippines. These historical developments helped build a foundation for large Eurasian communities in this region. Old Eurasian families in the Philippines mainly descend from the Spanish. While the oldest Indo families descend from Portuguese traders and explorers, some family names of old Indo families include Simao, De Fretes, Perera, Henriques, etc

Dutch and English roots (17th and 18th century)

With the decline of the Portuguese and Spanish global empires after the beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch and English maritime merchants started establishing an equally comprehensive global network of trading posts. In 1602 the Dutch founded the first ever joint stock multinational firm, called the United East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC). The VOC’s main aim was to generate profit from international trade with South and South East Asia, also known then and later as the East Indies. The VOC established a dominant European presence on for example the island of Java, as well as on numerous islands north and east of Java. Their English counterparts did the same west of Java in Singapore and Malaya.

Originally, most Dutch VOC employees were traders, accountants, sailors and adventurers and may have thought of themselves as temporary sojourners. British and other Europeans also settled there, usually as traders or professionals. Most of the settlers in the 18th and early 19th centuries were men, without wives. Considerable mixing occurred with the local inhabitants. The VOC and later the colonial government to a certain extent encouraged this, partly to maintain their control over the region. The existing Indo (or Mestizo) population of Portuguese descent was therefore welcome to integrate. A relatively large Indo-European society started to develop in the East Indies. Although most of its members became Dutch citizens, in offset their culture was strongly Eurasian in nature, with equal focus on both the native Asian and foreign European heritage. In fact 'European' society in the Indies was dominated by this Indo culture into which non native born European settlers integrated. This would change coming the formal colonization by the Dutch in the 19th century.

Colonial history (19th and 20th century)

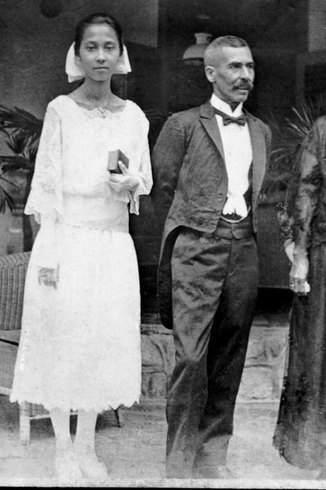

Jan Fransz & daughter.

Dutch East Indies

After the bankruptcy of the privately owned VOC at the end of the 18th century the Dutch state took over its debts, as well as its possessions. The small country of the Netherlands commenced with replacing the strong VOC presence in the East Indies and established colonial dominance from the island of Sumatra bordering the Malaysian peninsular in the west, the island of Celebes (now called Sulawesi) bordering the Philippines in the north, to Netherlands New Guinea (now called West Papua) bordering the continent of Australia in the South-East. In around 150 years this evolved into the colony called the Dutch East Indies (Dutch: Nederlands-Indië). The creation of this governmental and administrative entity became the foundation of the independent state of Indonesia in the middle of the 20th century. In this period a large Indo community developed that was recognized by Dutch law as European. The majority of legally acknowledged Europeans in the Dutch East Indies were in fact Indo Eurasian. During this time the already existing Indo population was mainly complimented by the offspring of Dutch, Belgian and German soldiers who served in the Netherland East Indies Army (KNIL). Family names include: Schwartzman and Meijs.

Indo influence on the nature of colonial society only waned after the end of the World War I and the opening of the Suez Canal, when there was a substantial influx of white Dutch families. In the Dutch East Indies a large Indo movement led by the Indo European Alliance voiced the idea of independence from the mother country, however only a small Indo minority led by Ernest Douwes Dekker and P.F.Dahler joined the indigenous independence movement. Unlike many South American colonies which obtained independence after the independence wars led by Simon Bolivar in the 19th century, the Indonesian archipelago became independent only after World War II.

Japanese occupation

During World War II the European colonies in South East Asia were annexed by the Japanese Empire. After the Japanese army defeated the British armed forces in the Malay peninsula, they invaded the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonial army (Dutch: Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger, KNIL) was unequipped to stop the modern Japanese war machine. Japan's early victories destroyed the myth of European superiority and initially the Asian peoples welcomed the new occupying power, until it became apparent that Dutch colonial rule was only to be replaced by Japanese colonial rule. The Japanese occupying powers soon started to eradicate anything reminiscent of European government. All Europeans were put in Japanese concentration camps. First the POW’s, then all male adults and finally all females and adolescents were interned. The Japanese failed in their attempts to win over the Indo community and Indos were made subject to the same forceful measures.

"Nine tenths of the so called Europeans are the offspring of whites married to native women. These mixed people are called Indo-Europeans… They have formed the backbone of officialdom. In general they feel the same loyalty to Holland as do the white Netherlanders. They have full rights as Dutch citizens and they are Christians and follow Dutch customs. This group has suffered more than any other during the Japanese occupation.” Official US Army publication for the benefit of G.I.’s, 1944.

During the Japanese occupation leaders of the Indonesian independence movement cooperated with the Japanese to realise an independent nation. Only after Japan's defeat by the Allied forces were these leaders able to declare the Republic of Indonesia. The majority of the Indo community was either captive or in hiding and remained oblivious to these developments. The Indo community at large did not participate in the Indonesian independence movement. The main revolutionary leader Sukarno was declared the first president of the Republic in 1945. But to the Dutch government he was a collaborator and could not be accepted as an official counterpart. The legitimacy of the Republic and its president remained disputed until 1949 when the Netherlands finally recognised Indonesia’s independence.

After the bankruptcy of the privately owned VOC at the end of the 18th century the Dutch state took over its debts, as well as its possessions. The small country of the Netherlands commenced with replacing the strong VOC presence in the East Indies and established colonial dominance from the island of Sumatra bordering the Malaysian peninsular in the west, the island of Celebes (now called Sulawesi) bordering the Philippines in the north, to Netherlands New Guinea (now called West Papua) bordering the continent of Australia in the South-East. In around 150 years this evolved into the colony called the Dutch East Indies (Dutch: Nederlands-Indië). The creation of this governmental and administrative entity became the foundation of the independent state of Indonesia in the middle of the 20th century. In this period a large Indo community developed that was recognized by Dutch law as European. The majority of legally acknowledged Europeans in the Dutch East Indies were in fact Indo Eurasian. During this time the already existing Indo population was mainly complimented by the offspring of Dutch, Belgian and German soldiers who served in the Netherland East Indies Army (KNIL). Family names include: Schwartzman and Meijs.

Indo influence on the nature of colonial society only waned after the end of the World War I and the opening of the Suez Canal, when there was a substantial influx of white Dutch families. In the Dutch East Indies a large Indo movement led by the Indo European Alliance voiced the idea of independence from the mother country, however only a small Indo minority led by Ernest Douwes Dekker and P.F.Dahler joined the indigenous independence movement. Unlike many South American colonies which obtained independence after the independence wars led by Simon Bolivar in the 19th century, the Indonesian archipelago became independent only after World War II.

Japanese occupation

During World War II the European colonies in South East Asia were annexed by the Japanese Empire. After the Japanese army defeated the British armed forces in the Malay peninsula, they invaded the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonial army (Dutch: Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger, KNIL) was unequipped to stop the modern Japanese war machine. Japan's early victories destroyed the myth of European superiority and initially the Asian peoples welcomed the new occupying power, until it became apparent that Dutch colonial rule was only to be replaced by Japanese colonial rule. The Japanese occupying powers soon started to eradicate anything reminiscent of European government. All Europeans were put in Japanese concentration camps. First the POW’s, then all male adults and finally all females and adolescents were interned. The Japanese failed in their attempts to win over the Indo community and Indos were made subject to the same forceful measures.

"Nine tenths of the so called Europeans are the offspring of whites married to native women. These mixed people are called Indo-Europeans… They have formed the backbone of officialdom. In general they feel the same loyalty to Holland as do the white Netherlanders. They have full rights as Dutch citizens and they are Christians and follow Dutch customs. This group has suffered more than any other during the Japanese occupation.” Official US Army publication for the benefit of G.I.’s, 1944.

During the Japanese occupation leaders of the Indonesian independence movement cooperated with the Japanese to realise an independent nation. Only after Japan's defeat by the Allied forces were these leaders able to declare the Republic of Indonesia. The majority of the Indo community was either captive or in hiding and remained oblivious to these developments. The Indo community at large did not participate in the Indonesian independence movement. The main revolutionary leader Sukarno was declared the first president of the Republic in 1945. But to the Dutch government he was a collaborator and could not be accepted as an official counterpart. The legitimacy of the Republic and its president remained disputed until 1949 when the Netherlands finally recognised Indonesia’s independence.

Post colonial history (1945–1965)

Arrival of the "Castel Felice" with Indo (Eurasian) repatriates from Indonesia on Lloydkade, Port of Rotterdam. Netherlands, Rotterdam, May 20th, 1958.

Indonesian Independence

At the end of World War II Europe’s colonial presence around the world quickly declined. The Dutch tried to vainly hang on to their colonial possessions in Indonesia during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1948), but lost the military and still later political battles they waged, to the newly founded Republic of Indonesia. In the end the Dutch were completely ousted from the archipelago. Although native to the country the Indo community was intertwined with Dutch rule and their intermediary role between colonial government and the majority of local society became obsolete. Notwithstanding many Indos had been active in the resistance movement fighting Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, only a minority was actively involved in the Indonesian revolution. After 400 years the Indo community in Indonesia dissolved. The founding of the Republic of Indonesia directly resulted in the Indo Diaspora. In contrast, the United Kingdom managed to hold on to their colonies in South East Asia until 1957 (Malaya) and 1963 (Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore) and were able to maintain the Commonwealth with the British sovereign as the titular head of this organisation. In Singapore the Eurasian community is acknowledged as a separate ethnic group

Indo diaspora

During and after the Indonesian National Revolution, which followed the Second World War, (1945–1965) around 300,000 people, pre-dominantly Indos, left Indonesia to go to the Netherlands. This migration was called repatriation. The majority of this group had never set foot in the Netherlands before.

The migration pattern of the so called Repatriation progressed in five distinct waves over a period of 20 years:

At the end of World War II Europe’s colonial presence around the world quickly declined. The Dutch tried to vainly hang on to their colonial possessions in Indonesia during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1948), but lost the military and still later political battles they waged, to the newly founded Republic of Indonesia. In the end the Dutch were completely ousted from the archipelago. Although native to the country the Indo community was intertwined with Dutch rule and their intermediary role between colonial government and the majority of local society became obsolete. Notwithstanding many Indos had been active in the resistance movement fighting Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, only a minority was actively involved in the Indonesian revolution. After 400 years the Indo community in Indonesia dissolved. The founding of the Republic of Indonesia directly resulted in the Indo Diaspora. In contrast, the United Kingdom managed to hold on to their colonies in South East Asia until 1957 (Malaya) and 1963 (Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore) and were able to maintain the Commonwealth with the British sovereign as the titular head of this organisation. In Singapore the Eurasian community is acknowledged as a separate ethnic group

Indo diaspora

During and after the Indonesian National Revolution, which followed the Second World War, (1945–1965) around 300,000 people, pre-dominantly Indos, left Indonesia to go to the Netherlands. This migration was called repatriation. The majority of this group had never set foot in the Netherlands before.

The migration pattern of the so called Repatriation progressed in five distinct waves over a period of 20 years:

- The first wave, 1945–1950: After Japan's capitulation and Indonesia’s declaration of independence around 100,000 people, many former captives that spent the war years in Japanese concentration camps and then faced the turmoil of the violent Bersiap period, left for the Netherlands. Although Indos suffered severely during this period, with 20,000 people killed over 8 months in the Bersiap period alone, the great majority only left their place of birth in the next few waves.

- The second wave, 1950–1957: After formal Dutch recognition of Indonesias independence many civil servants, law enforcement and defence personnel left for the Netherlands. The colonial army was disbanded and at least 4,000 of the South Moluccan price soldiers and their families were also relocated to the Netherlands. The exact number of people that left Indonesia during the second wave is unknown.

- The third wave, 1957–1958: During the political conflict around the so called ‘New-Guinea Issue’ Dutch citizens were declared undesired elements by the young Republic of Indonesia and around 20,000 more people left for the Netherlands.

- The fourth wave, 1962–1964: When finally the last Dutch ruled territory i.e. New Guinea, was released to the Republic of Indonesia. Also the last remaining Dutch citizens left for the Netherlands, including around 500 Papua civil servants and their families. The total number of people that migrated is estimated at 14,000.

- The fifth wave, 1949–1967: During this overlapping period a distinctive group of people, known as Spijtoptanten' (Repentis), that originally opted for Indonesian citizenship found that they were unable to integrate into Indonesian society and also left for the Netherlands. In 1967 the Dutch government formally terminated this option.Of the 31,000 people that originally opted for Indonesian citizenship 25,000 withdrew their decision over the years

Contemporary history (20th and 21st century)

Relocation and assimilation

Many Indos that had left for the Netherlands often continued the journey of their Diaspora to warmer places in the West like for instance California and Florida in the United States of America. Exact numbers relating to Indo immigrants in other major immigration countries like Canada and New Zealand are less well documented. A 2005 study estimates the number of Indos that went to Australia around 10,000. Research has shown that most Indo immigrants are assimilating into their host societies.

In contrast to Indonesia the Eurasian communities of Malaysia, in particular Singapore are flourishing, offering their native Eurasian population a wide range of community services including: Heritage and culture studies and exhibitions, family support services, social assistance programs, youth mentoring programs, scholarships and subsidies. Singapore's second president Benjamin Sheares was a Eurasian. Many political leaders in East Timor are Eurasian Mestizo including the former and current President, Xanana Gusmao and José Ramos-Horta.

An undetermined future

The Indos are a people of mixed Indonesian and European ancestry that developed over a period of more than 400 years. Although all family names are uniformly European, their ethnic composition varies from diverse European peoples such as the Portuguese, Dutch, Belgian, French and German, with some British; and equally diverse Indonesian peoples such as Javanese, Sundanese, Ambonese, Manadonese, Moluccan, Borneonese and Sumatran. The variety in their ethnic composition and the fact that they are spread out all over the globe makes it difficult to define a uniform Indo culture let alone predict its future.

The older an Indo family is, the harder it becomes to pinpoint an actual percentage of either pure European or Indonesian blood. In most cases this is practically impossible to determine. As Indo culture evolves, steered by the path of the Indo Diaspora, each new generation of Indos keeps integrating more and more into their new homelands. Increasingly the issue of an Indo identity is becoming a matter of personal choice and not a given into which an individual is born.

The new generations will determine if their legacy will become more than a historical footnote.

Many Indos that had left for the Netherlands often continued the journey of their Diaspora to warmer places in the West like for instance California and Florida in the United States of America. Exact numbers relating to Indo immigrants in other major immigration countries like Canada and New Zealand are less well documented. A 2005 study estimates the number of Indos that went to Australia around 10,000. Research has shown that most Indo immigrants are assimilating into their host societies.

In contrast to Indonesia the Eurasian communities of Malaysia, in particular Singapore are flourishing, offering their native Eurasian population a wide range of community services including: Heritage and culture studies and exhibitions, family support services, social assistance programs, youth mentoring programs, scholarships and subsidies. Singapore's second president Benjamin Sheares was a Eurasian. Many political leaders in East Timor are Eurasian Mestizo including the former and current President, Xanana Gusmao and José Ramos-Horta.

An undetermined future

The Indos are a people of mixed Indonesian and European ancestry that developed over a period of more than 400 years. Although all family names are uniformly European, their ethnic composition varies from diverse European peoples such as the Portuguese, Dutch, Belgian, French and German, with some British; and equally diverse Indonesian peoples such as Javanese, Sundanese, Ambonese, Manadonese, Moluccan, Borneonese and Sumatran. The variety in their ethnic composition and the fact that they are spread out all over the globe makes it difficult to define a uniform Indo culture let alone predict its future.

The older an Indo family is, the harder it becomes to pinpoint an actual percentage of either pure European or Indonesian blood. In most cases this is practically impossible to determine. As Indo culture evolves, steered by the path of the Indo Diaspora, each new generation of Indos keeps integrating more and more into their new homelands. Increasingly the issue of an Indo identity is becoming a matter of personal choice and not a given into which an individual is born.

The new generations will determine if their legacy will become more than a historical footnote.

Historical pictures

Historical pictures from the Dutch East Indies can be found on the Wikimedia foundation's photo forum facilitated by the Dutch Tropenmuseum.

Click here: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Images_from_the_Tropenmuseum

Image on the left shows:

Opening of the Colonial Institute Amsterdam, now known as the Tropenmuseum and KITLV, 1926.

Click here: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Images_from_the_Tropenmuseum

Image on the left shows:

Opening of the Colonial Institute Amsterdam, now known as the Tropenmuseum and KITLV, 1926.

|

|

|